Over 1000 people packed into a London college to take part in a day of analysis of the state of the British economy. And hundreds had been turned away. This was a conference called by the new left-wing leadership of the opposition Labour party in Britain. The hardworking and dedicated activists within the Labour party that had backed Jeremy Corbyn, the new leftist leader, had turned out in droves to discuss with due intent what is wrong with capitalism in Britain and what to do about it. It was an unprecedented event: the leadership of the Labour party calling a meeting to discuss economics and economic policy and allowing party members to discuss.

Labour’s finance leader, John McDonnell opened the conference by saying the aim of the various sessions was to see how Labour could “transform capitalism” into delivering a “fairer, democratic sustainable prosperity shared by all”. We needed to “rewrite the rules” of capitalism to make it work for all. He argued the British capital was failing to invest for growth and jobs. We needed to break with the ‘free market’ ideology of the neo-liberal agenda and “reshape the narrative” with “new economics”.

What was this new economics? Well, I’m afraid it was not new but really a rehash of old Keynesian arguments and policy proposals. As McDonnell said, the aim was to “transform capitalism” with new rules and state intervention, not to replace it.

The key note speaker at the conference was left Keynesian Cambridge University economist Ha-Joon Chang. He delivered an entertaining and amusing presentation, the gist of which he had already written in an article for the British liberal Guardian newspaper that week. Chang presented a compelling argument that the strategy adopted by previous right-wing and Labour governments of weakening manufacturing and industry in favour of finance, property and other unproductive services (in other words, turning Britain into a rentier economy) was a big mistake.

British capitalism was failing to compete in world markets with a record high deficit on trade with the rest of the world – see graph below (all graphs in this post have been researched by me and are not those of any speaker).

And its people had seen no rise in real incomes for eight years since the global financial collapse. British economic strategists reckon that the UK economy did not need a thriving industrial base and could rely on its financial services – just like Switzerland. The irony was that Switzerland is actually the most industrialised economy in the world, as measured by manufacturing output per person (see below).

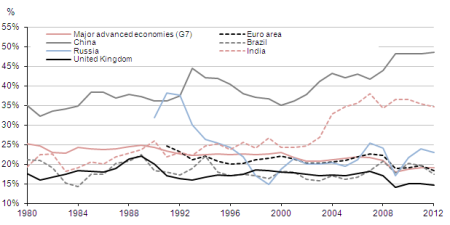

In contrast, British manufacturing has been in fast decline as a share of total output among major capitalist economies.

Chang reckoned Labour should aim to boost industry, R&D and investment, because those sectors can raise productivity for all sectors and incomes. But he did not expand on how that was to be done in an economic world where banks and hedge funds rule, loans are made for property, while businesses hold back from investment.

In the finance workshop, the poverty of analysis and policy was very evident. The main speakers were Frances Coppola, who has worked as an economist in many banks and now runs a blog on economics; and Anastasia Nesvetailova, who is a professor at the City of London university on finance and has spoken before at the series of ‘new economics’ meetings run by the Labour party.

Both speakers basically told hundreds before them that the regulation of the banks would not avoid a future financial crash – indeed by making regulation ‘too tight’, it was strangling the ability of the banks to lend. A financial transaction tax would not work either in controlling risk-taking by banks, particularly in new finance areas outside regulation. Breaking up the big banks or separating their speculative operations from basic banking would not work either. Indeed, nothing would work to avoid yet another crash in the future: “we just had to prepare for one”!

So our finance experts had not a clue what to do. Staring them in the face was the obvious answer. If the big banks are still engaged in risk activities, in greedy laundering and in paying grotesque salaries to their top executives, despite regulation, why not take them into public ownership under democratic control so that banking becomes a public service for the people to help investment and growth? This policy move was never even considered by these banking experts and yet Britain’s own firefighters union have produced an analysis showing why it was the best way forward, which was formally approved by the trade union federation. I was told that state-owned banks would not work because they are corrupted by politicians – sure, as opposed to privately-owned banks that are as pure as snow.

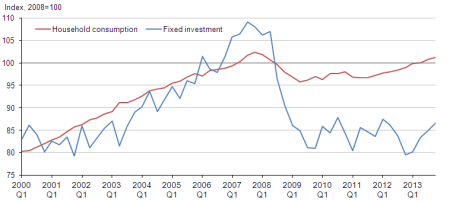

At least in the session on fiscal and monetary policy, Michael Burke provided a coherent account of how the weak economic recovery in the major economies including the UK was not due to a lack of consumer demand as the Keynesian ‘experts’ keep arguing, but to one major factor: the failure of business to invest. The graph below for the UK shows how it was investment that collapsed in the Great Recession not consumption. It was the same story in all the major economies.

The large companies were hoarding cash, small business were just hanging on and governments were cutting back on public sector investment. Indeed, British capital has the lowest level of investment to GDP of the major capitalist economies (see black line in graph below).

Weak and even falling investment had lowered growth rates and so held down incomes. The answer was a new plan for growth based on public investment.

The conclusion of the day’s conference screamed out to me. The capitalist sector had caused the crash, not the public sector. But the public sector had to pay with increased debt and a reduction in the role of the state as support for growth and as a safety net for those who lost their jobs, homes and incomes.

So instead of trying to “transform capitalism”, Labour needs to develop a programme to replace capitalism by bringing into public ownership the major banks and business sectors under democratic control to be integrated into a plan for investment in people’s needs not profit. Instead, Labour’s advisers and experts offered just some old ideas that had been tried and failed before to direct or regulate capitalism to make it work better. No new economics there.

No comments:

Post a Comment